In advance of the premiere of the commissioned work In Posse, Arts Programme Curator Herb Shellenberger spoke with artist Charlotte Jarvis about her background, previous works and the development of In Posse. The artist also gives a preview of what to expect of its exhibition at Site Gallery for Sheffield Doc/Fest 2021.

"IT’S GOING TO BE A BIG, MESSY AND JOYOUS EJACULATION ALL OVERSITE GALLERY!"

HS: Going back to the start: did you want to be an artist when you were growing up? Or a scientist? When did these two disciplines merge for you?

CJ: I was always interested in both. I did all the A-levels for med school, and then decided that actually I would prefer to study art. I didn’t find a way of combining them until my Masters. I studied on a really extraordinary course which no longer exists - Design Interactions at the RCA. It’s difficult to define exactly what unified everyone who studied and taught on that course - we were a pretty mixed bunch - but broadly it was about using / reflecting on / critiquing science and technology in order to understand the experience of being a human. Or at least, that is what it was for me.

HS: In Posse is part of your series of works titled Corpus, in which you’ve spent the past decade approaching the body as a site of artistic experimentation and change. Could you give us some background on this series and how In Posse fits together with its previous chapters?

CJ: Corpus is a triptych of reproduction. In the first piece, Ergo Sum, I donated parts of my body to stem cell research. The donated specimens were taken to the lab in Leiden where they were transformed – medically metamorphosed – into induced pluripotent stem cells and from there into a range of completely different substances. A kind of second self was created, a self-portrait, a synecdoche, made from a collage of synthesized body parts. Brain, heart and blood all biologically ‘Charlotte’ but also distinctly alien to me.

For the second part of Corpus, Et in Arcadia Ego I grew a malignant tumor in vitro from healthy cells harvested from my body. The project aimed to examine mortality and create a dialogue with and about cancer. The title references a painting by Poussin from 1637-38. The painting depicts four Classical shepherds discovering a stone monument within an idealised Tuscan landscape. The shepherds are reading the engraving Et in Arcadia Ego (“Even in paradise I am here”). The edifice is a tomb, and the first person ‘I’ who speaks through the inscription is Death.

In Posse - the third part of Corpus - deals with reproduction in a literal sense by challenging who has possession over certain reproductive cells and fluids.

"BY ATTEMPTING TO MAKE SEMEN FROM ‘FEMALE’ CELLS, WE ARE INVENTING NEW SCIENCE."

Corpus aims to find alternative spaces of discourse for the human body. The first two parts, Ergo Sum and Et In Arcadia Ego, used stem cell research, genetic engineering and oncological technologies to place the body in between states - disrupting the site, mutating the contents, and confronting im/mortality. These pieces used my own cells to decontextualise existing scientific processes in order to reveal their social and emotional meaning. For In Posse we are once again using my cells to find ‘other’ spaces - placing my body at the intersection of sex and gender, but the piece is also an evolution from the previous two because, firstly, it utilises the cells of multiple women, trans and non-binary people (a collective act), and, secondly, it goes further than reframing existing technologies. By attempting to make semen from ‘female’ cells, we are inventing new science. The three parts of Corpus are a kind of crescendo - becoming more complex and asking harder ethical questions.

HS: Can you describe the seminal moment of In Posse? What was the starting point of this work which led you to the still-unfolding journey of making it? Since that beginning, you’ve gone on an odyssey in making this work across a number of countries, years, partners and developing ideas.

CJ: I had the idea when I was making Ergo Sum and we were growing lots of different things from my stem cells. I thought that if - in theory - you can grow any kind of cell from a stem cell, then you could certainly try to grow sex cells. It follows that if I could somehow change the gender of my stem cells I could then make sperm. At the time, the scientists I was working with thought that it would be fundamentally impossible - for complicated reasons I won’t go into here - but every couple of years or so I would check back in with them and ask if it could now be done. Eventually one of these scientists - the brilliant Christine Mummery - suggested that I talk to the researcher in the opposite office to hers in the Leiden University Medical Centre. That researcher is Prof. Susana Chuva de Sousa Lopes - my collaborator on In Posse.

I caught Susana at exactly the right time. Her research is perfectly placed for what I wanted to do - she looks at how the proto sex cells are formed in the foetus, and the part the chromosomes, amongst other things, have to play in this process. Furthermore, the project is well timed in a broader context; many labs were, and still are, attempting to grow sex cells from stem cells for use in fertility treatments. We can learn from all of this ongoing ground-breaking research and utilise it in our own project.

"I HAD THE IDEA OF INVITING MULTIPLE WOMEN, TRANS AND NON-BINARY PEOPLE TO DONATE THEIR BLOOD TO THE PROJECT. MAKING THE SEMINAL FLUID THIS BECAME A COLLECTIVE ACT – A SYMBOLIC STANDING TOGETHER IN REJECTION OF PATRIARCHAL HIERARCHY."

Having established a collaboration with Susana, there were two other moments that have really defined the project. Firstly, making the jizz. In Posse is about approaching semen as a symbol - one that has historically been used to solidify binary, traditional notions of sex and gender - and metamorphosing it so that it can be used to undermine patriarchal paradigms. The aesthetics of the symbol are important. When we think about how the semen-symbol has been used to signify power structures (consider, for example, the ubiquitous cum-on-face shot that crowns much pornography, and the power relationship that is communicated by it,) the physicality of the substance is conspicuous. Therefore, in order to use semen as a symbolic sculptural object I realised that I needed to develop “female” seminal plasma as well as sperm cells.

I developed the seminal plasma - the goo, the slime, the gunk, the cum - in Ljubljana with the Biotehna lab, which is part of Kapelica Gallery / Kersnikova Institute. We started by following pre-existing published ‘recipes’, of which there are many. However, all the papers we looked at used bovine plasma, which is derived from the blood of cows. I did not want the world’s first ‘female’ semen to also be cow semen, and so we decided to try replacing this substance with human blood plasma. It turned out that it is in fact quite easy to extract plasma from blood, and that you really don’t need a lot of blood. This opened up the possibility of including other people. I had the idea of inviting multiple women, trans and non-binary people to donate their blood to the project. Making the seminal fluid this became a collective act – a symbolic standing together in rejection of patriarchal hierarchy.

The final ‘seminal’ moment came as I was developing the form of the project for exhibition and performance with MU Hybrid Art House in Eindhoven. I wanted to find something messy, wet and joyful; to contrast the very anodyne lab aesthetic of much of this kind of art-making with a gunky, chaotic, sticky ejaculation! It was also important to me that the project communicated as much about the history of patriarchy as a possible future without it. It was at this point that I first read about the Thesmophoria - and this has really shaped how the project is experienced and communicated.

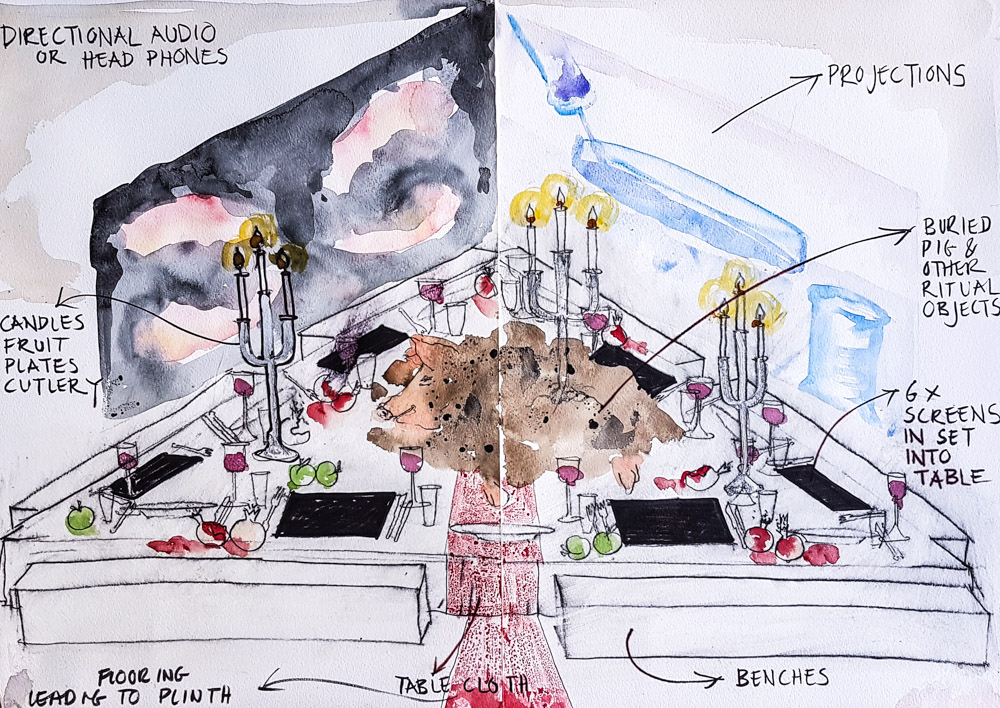

The Thesmophoria was the largest festival in the whole of ancient Greece - both in terms of geographical area and longevity. However, virtually nothing is known about the original festival because it was women-only - men were forbidden from participating or knowing about the rites and rituals involved; and thus it was completely undocumented. What we do know is that it was dedicated to the fertility goddess Demeter, her daughter Persephone and also Hecate: The three in one - the daughter, the mother and the crone. Most accounts agree that there was a feast of seeds and the burial of a pig, which gets exhumed and used to fertilise the fields. “Ritual obscenity” (which sounds exciting) and serpentine / phallic offerings also seem to have featured.

So, the form In Posse is shared, performed and exhibited in is a reenactment and reimagining of this ancient Greek fertility festival. This is where myself and participating women, trans and nonbinary people call the female semen into existence. The festivals are designed and executed by participants over a number of days. They build on the scant extant details and rumors about the Thesmophoria and create new collaborative rites and rituals around the donation of blood and associated laboratory protocols involved in making the project. All the festivals involve some kind of journey away from the site of “normal life” - often a trip into the wilderness or Katabasis (journey to the underworld). Participants get to decide for themselves how much or little they wish to document and share with the public.

HS: Could you tell us about the discussions that led to the first part of the work: growing spermatozoa from your body?

CJ: One of the first conversations I had with Susana was about the impossibility of scientifically defining sex. This is, in a roundabout way, how Susana first described it to me: Let us imagine you were trying to create a system to definitively define sex. There are perhaps four indicators you might use - the physical body, the brain, the hormones and the chromosomes. Let us say I was assigned the female sex at birth, and have subsequently identified as ‘female’ throughout my life. In terms of the physical body, if I discovered that I did not have ovaries, I would not ‘lose’ my sex. Equally, if, after puberty, I happened to be flat chested, the medical profession would not find it necessary to reassign my sex. If, later in life I undergo a hysterectomy I will not be considered less ‘female’ by any reasonable person.

"IF OUR SEX DOES NOT RESIDE IN THE BODY, THE BRAIN, THE BLOOD OR THE DNA… WHERE IS IT? WHAT IS IT?"

Secondly, let us say that I define myself as transgender. A little more than 9 people in every 100,000 define themselves as transgender, thats, by my calculations, 27,690,000 people in the world - more than the population of Australia. The idea of a ‘gendered brain’ has been thoroughly debunked by numerous scientific studies and it would be wrong to diagnose me as mad, mistaken or suffering from a neurological disease. ‘Male’, ‘female’ and non-binary brains have the same structure and, crucially, plasticity. Brains reflect the lives of their owners far more than their sex. It’s important to aknowledge here that despite this the transgender community continue to suffer prejudice and discrimination at the hands of the ignorant.

Thirdly, in terms of hormones, there are many people who identify as ‘female’ – myself included – who have higher levels of testosterone than the average male identifying person and vice versa. Furthermore, when I go through the menopause and stop producing oestrogen, I do not intend to reassign my sex, and I would be rightfully outraged if someone else suggested that I should.

Finally, we come to the chromosomes - considered by many to be the last bastion of binary sex determination. But, yet again, here we find that things are far from clear - the water is muddy and opaque. When Susana and I started In Posse, one of the first things we did was check my chromosomes, and this is why. I could have been born with the opposite chromosomes to my phenotypical sex. This might mean that I had grown up with a penis and testicles, identifying as ‘male’ but later discovered that I have XX chromosomes (‘XX’ being the genetic marker of what we describe as genetically ‘female’, whilst ‘XY’ is ‘male’). Equally I could have a womb and ovaries but discover that my chromosomes are, in fact, XY.

So, the question Susana posed to me was… where is sex. If our sex does not reside in the body, the brain, the blood or the DNA… where is it? What is it? The scientific process we have designed for making In Posse draws on some of the examples above. It is also an attempt to illustrate the questions we are left with when we consider sex; to further contaminate the water and problematise the binary.

"IT’S GOING TO SIT SOMEWHERE BETWEEN A FEAST, A CINEMA AND AN ALTER."

HS: During the development of In Posse, you became pregnant, experienced labour and are now a mother. How has this shifted or changed your perspectives from the earlier stages of the project?

CJ: In Posse, and all my work over the past decade, is broadly about enacting a transformation through collaborative practice. I have been seeking some kind of scientific transubstantiation; attempting to shift the context within which we view scientific advancement to reveal broad existential questions, and to challenge pre-existing assumptions about human bodies. What has been a great surprise to me over the past year is how effectively pregnancy and birth does these things already.

My experience of pregnancy, labour and motherhood has been a palpable demonstration of the body's mutability. It has required me to inhabit the positions of being both binary and singular at the same time. I have possessed new and different body parts, multiple hearts, extra ovaries and a new brain. I have been forced to accommodate and love a parasite so that the boundary between myself and her was completely opaque. During labour I was animal and god, the two of us existing somewhere between life and death. My brain has subsequently been hijacked by this new being - some as yet dormant part of my mind took over and usurped my logical brain when we became two, so that at least for a couple of weeks I felt possessed - a body repurposed to serve another.

Before having a child I would often talk about mutating bodies, hybridised beings, additional body parts, alien DNA and of blurring the physical and genetic boundaries between individuals in the context of radical new science and technology. It is funny to me that, in the last couple of years, whilst myself and multiple collaborators have been working on In Posse and expending huge amounts of time, money and energy on creating a transgressive, activistic, queer form of reproduction, my body managed it on its own in just 9 months. In a recent panel discussion I took part in, I was asked why I think it is that we have, throughout our history, traditionally failed to philosophise, analyse or to learn from pregnancy and birth in this way. The simple answer is, of course, patriarchy.

"WE ARE IN FLUX, OUR BODIES CONSTANTLY CHANGING, ADAPTING, RESPONDING, MORPHING AND WITHOUT STABLE BORDERS."

I think that, rather than theorizing around its transformative changing nature, writers, philosophers, doctors etc. have discounted the ‘female’ body because of its mutability. ‘Male’ bodies are historically the gold standard. It is Vitruvian MAN, not woman after all. One feature of the “male” body in contrast to the “female”, trans or non binary body is its comparative stability. We tend to consider bodies, or optimal bodies at least, as fixed. Their power (their ‘maleness’) is derived from their stability - these bodies do not change. David is carved into marble - perfect and preserved. I would hypothesize that this preference for the constant body is also one reason why we have traditionally treated aging bodies with such distaste.

However, even if we fail to take the macro, lived experience of over 50% of the population of the planet into account - far more once we consider the aging body - new science and technology is, once again, forcing us to shift our perspective. Our understanding of bodies on a molecular and quantum level is distinctly liminal. Dipole charges attract or repel energy. The sensory system detects subtle differences in these "dipoles" and responds by literally moving the boundaries of objects within the body - we are in flux, our bodies constantly changing, adapting, responding, morphing and without stable borders. Quantum biology asks us Where does the body begin and end? Is there such a thing as a definable body? And Are any organisms finite within a network of life?

HS: Without giving it all away, can you give our audiences a taste of what’s in store for them in the upcoming presentation of In Posse at Sheffield Doc/Fest and Site Gallery in June?

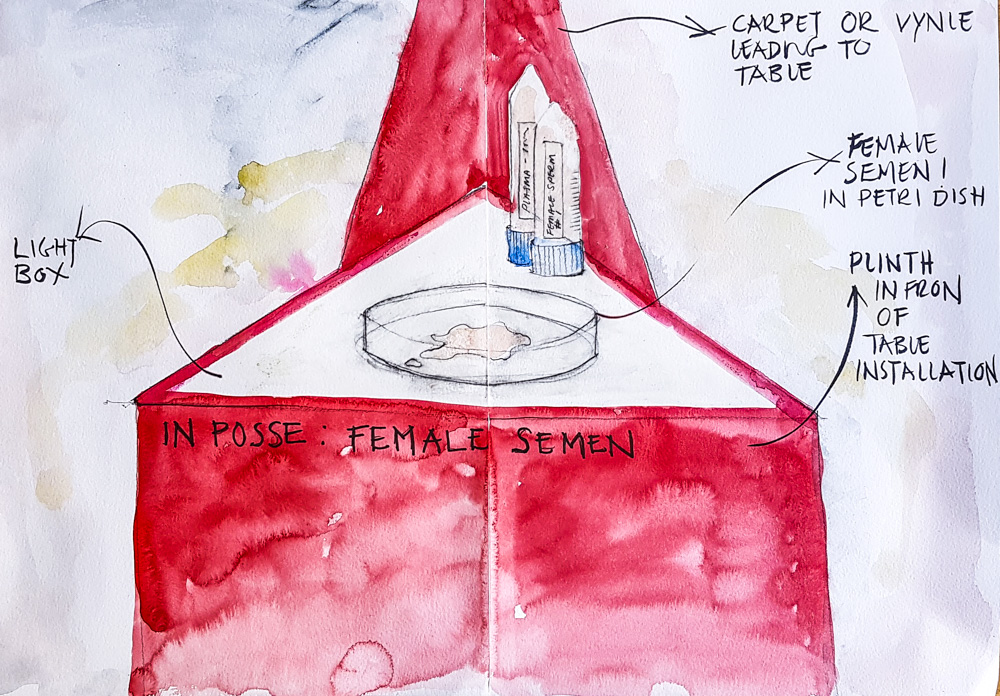

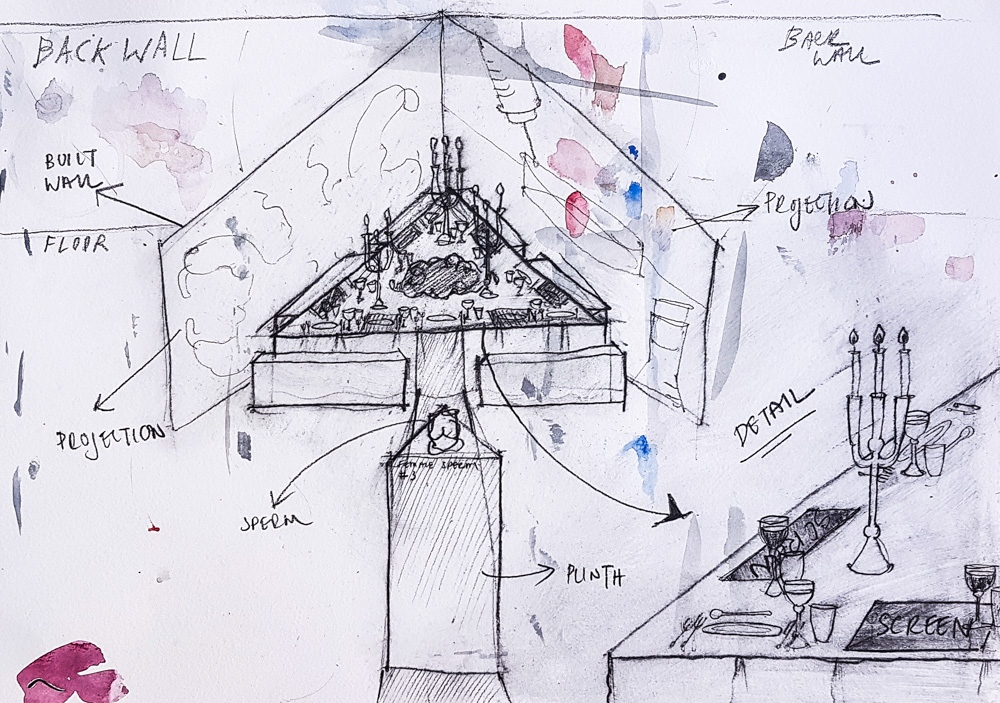

CJ: It’s going to be a big, messy and joyous ejaculation all over Site Gallery! We are working on an ambitious installation that incorporates multiple screens, projections, elements of the Thesmophoria, lab equipment and of course the ‘female’ semen itself. It’s going to sit somewhere between a feast, a cinema and an alter. There are days and days of film documentation from the past few years which will be featuring in the installation - footage of blood donations, midnight processions into the forest, mixing seminal plasma on my pregnant belly, cell culturing in Leiden, burying a pig, wild moon-lit dancing and watching semen drift away into the Aegean. There will also be a Thesmophoria taking place in Sheffield during the festival.

In Posse, which has been produced in collaboration with Dr. Susana Chuva de Sousa Lopes (Leiden University Medical Center), Kapelica Gallery / Kersnikova Institute (Ljubljana) and MU Hybrid Art House (Eindhoven), will premiere as a multi-channel video installation at Site Gallery (subject to restrictions easing) as part of our free Arts Programme: 4-13 June 2021. The exhibition of In Posse will also be displayed on our online exhibition platform. Furthermore, the exhibition will be complemented by a live performance during the festival and will take the form of a Thesmophoria festival enacted with women, trans and non-binary individuals.

Click here to find out more about In Posse.