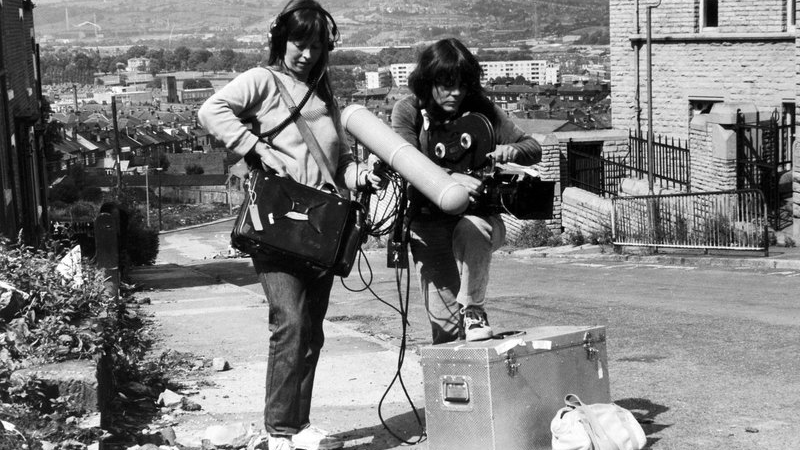

Filming in Walkley (L-R: Christine Bellamy and Jenny Woodley). Image - Caroline Laidler.

We are excited to be screening three films by the pioneering film collective, Sheffield Film Co-op, on Thursday 15 June at Showroom Cinema as part of this year’s festival.

The screening will be followed by a panel discussion featuring members of the Sheffield Film Co-op Jenny Woodley and Chrissie Stansfield, alongside archivist Alex Glen Wilson, hosted by Rachel Pronger.

Curated by Invisible Women, the programme brings together three short films spanning the Sheffield Film Co-op’s history, from their early DIY activist work to innovative hybrid experiments and compelling investigative documentaries.

In an interview with Sheffield Film Co-op members Jenny Woodley and Chrissie Stansfield originally published in the Sheffield Tribune, one of our 2023 Festival Programme Advisors Rachel Pronger digs deep into the collective’s history. Read on to learn more.

When Chrissie Stansfield first moved to Sheffield in 1980, she never dreamed that this relocation would set her on the road to becoming a filmmaker. “I had nothing to do with film,” Stansfield remembers. “I was actually a social worker. I went to university late and moved up to Sheffield because I thought it would be a nice place to be.”

Sheffield in the early eighties was a particularly nice place to be if you were interested in feminist activism. The city has a long history of radical female-led organising, spanning back to the foundation of the UK’s first women’s suffrage organisation in the 1850s. By the time Stansfield arrived, more than a century later, the city had earned a reputation as a socialist republic, a hub for community activism, grassroots feminism and left-leaning resistance to the newly appointed Thatcherite government.

Through a twist of fate — and an advert in the feminist magazine Spare Rib — Stansfield ended up lodging in the house of Jenny Woodley, a working mother and local organiser. Just a few years earlier, Woodley had played a pivotal role in founding one of the UK’s most significant feminist film collectives. This chance encounter would change the course of Stansfield’s life and career, and bind the two women together as lifelong friends and collaborators.

The Sheffield Film Co-op (L-R: Christine Bellamy, Lynne Colton, Sue Cane, Nina Kellgren, Hilary Buchanan, Chrissie Stansfield). Image: Caroline Laidler.

The story of the Sheffield Co-op begins in the late 1960s, with the first stirrings of second wave feminist organising in the city. The foundation of the Sheffield Women’s Liberation Group, part of a nationwide flowering of consciousness-raising organisations during this period, brought together a group of local women united in frustration at the misogynist status quo. Together they held meetings and support groups, and published a regular DIY newsletter, complete with hand drawn illustrations, which explored pressing — and still highly relevant — issues such as equal pay, violence against women, rape culture and pornography.

Woodley was an active member of the Sheffield’s Women Liberation Group, when they were approached by a sympathetic commissioner, who invited the women to make a series of radio plays for schools exploring second wave feminism. “This suited us perfectly because we were fed up,” she remembers. “The media at that time was only into Women’s Lib and bra burning. We thought ‘blow it!’ If we can’t get any serious coverage, let’s have a go at doing some ourselves.”

That series, Not Just a Pretty Face, was well received and gave the group a taste for media work. When soon afterwards a local television station, Sheffield Cablevision, began advertising for volunteers, four of the women — Woodley, Barbara Fouwkes, Christine Bellamy and Gill Booth — seized the opportunity, laying the groundwork for the organisation that would eventually evolve into the Sheffield Film Co-op.

A still from ‘Women and Children Last’, 1971: a woman being interviewed about how easy she finds it to navigate Sheffield city centre with a pushchair and children in tow. Image: ‘Women and Children Last’/Vimeo.

The UK film industry of the 1970s was overwhelmingly male-dominated, and none of the founding members were professional filmmakers. Even within the more open world of public access television, it was a struggle to be taken seriously. The station manager’s “whole claim to fame was being the voiceover for some razor blade commercials” remembers Woodley, a wry detail which hints rather deliciously at the testosterone-heavy atmosphere at Cablevision — this same manager referred to the women as his “four ordinary housewives.” Yet it was that very “ordinariness” which was to prove the women’s superpower. At a time when little media spoke directly to everyday female experiences, the women sought to make programmes that would address the unglamorous issues shaping their daily lives.

All the founding members of the Co-op were young mothers with children mostly under school age. Woodley herself was 35 with two children when she first began working on films with the group. As a result, the women were passionate about making films which would raise awareness of the challenges they faced as caregivers navigating the city. Their first film set the tone. Women and Children Last (1971) looks at the challenges faced by mothers attempting to navigate the newly redeveloped Sheffield city centre. By asking who the city is for, the women hit upon still topical ideas about gender biases in urban infrastructure. A sequence in which one mother climbs railings in order to hang a “buggies not welcome” sign above a set of steps reveals a glimpse of mischievous spirit that would go on to become a signature of the collective.

It didn’t take long for that subversive energy to start ruffling feathers. In 1975, the women decided to make a film about abortion in response to a parliamentary bill which threatened to restrict access. Abortion had only recently been decriminalised, and Cablevision’s male staff baulked at the idea of making a programme about such a contentious topic. In response, the women broke away. With the help of Barry Callaghan, who ran the film department at Sheffield Polytechnic, the women learned to work with 16mm film and applied for funding to form a collective. The Sheffield Film Co-op was officially born.

A still from ‘A Woman Like You’ (1976). Image: ‘A Woman Like You’/Vimeo.

A Woman Like You (1976) would set the tone for the Co-op’s next phase. Blending dramatised scenes with interviews, this sensitive docudrama follows a married mother as she attempts to secure an abortion through the NHS. The film scrupulously avoids sensationalism, instead realistically depicting the claustrophobia of motherhood, the condescension of male doctors — the protagonist’s GP describes her as a “fit and healthy girl” — and the hurdles placed in the way of women exercising their right to choose. By focusing on a mother who is pursuing an abortion with the support of her husband, the film also challenges tabloid stereotypes.

The Co-op followed A Woman Like You with a series of films which took similarly bold approaches to feminist issues. Jobs for the Girls (1978) examines gender discrimination in the jobs market, while A Question of Choice (1982) discusses the experiences of working class women juggling childcare and employment. Particularly striking is That’s No Lady (1977) which focuses on domestic violence.

Scenes of a woman living with an abusive husband are intercut with footage of a comedian telling sexist jokes at a working men’s club, drawing a direct link between gendered violence and a culture of casual misogyny. “That was our most controversial film I think,” remembers Woodley. “It provoked a lot of discussion because we were showing things like the kind of conversation blokes might have at the pub. I can remember when we were showing that film to a community group, there was a woman sitting near the front. I overheard her turn to the woman sitting next to her and saying ‘my husband never tells me how much he earns’ under her breath.”

On the whole, the members of the Co-op generally enjoyed more supportive relationships with their partners. “A lot of the blokes were entirely supportive of the kind of films that we were making,” says Woodley, mentioning that several of the women’s partners ended up appearing in films, taking small roles playing the parts of unsupportive doctors and solicitors.

A still from ‘Jobs for the Girls’ (1978). Photo: ‘Jobs for the Girls’/Vimeo.

Woodley’s own husband pops up as the sexist stand up in That’s No Lady. Woodley remembers showing the film at Yorkshire Television. “One of the employees was lacing up the film for us in the projection booth, and afterwards he turned to me and said, ‘Wow where did you find that absolutely amazingly awful comedian,’” she laughs. “And I said proudly, ‘that’s my partner! It’s alright, he was using a script…’”

As this subject matter suggests, the Co-op saw their work as an extension of second wave feminist organising. The demands of the liberation movement — abortion on demand, equal pay, free nursery care and free contraception — were reflected in the films they made and in the way they worked. The women took turns to take on different roles on each project and established their own creches, sharing childcare to make sure mothers could be equally involved in production. This was filmmaking as activism, consciousness-raising as an art form.

Part of that feminist philosophy, was the Co-op’s commitment to centring female voices and training female filmmakers. “There wasn’t a strict rule that we must not have men working on our productions,” says Stansfield, who went on to join the Co-op in the early 1980s. “There happened to be some quite enlightened men around at the beginning, who were quite happy to be supportive to projects that were under the control of women.” She explains that they did reach a point where they drew in professional freelance women to train them. “The whole approach was about creating opportunities for women’s ideas to come through,” she continues, “and also opportunities for women to increase their skills and go on to make their own projects.”

The feminist principles of the collective were also reflected in their consensual approach to decision making. Although Stansfield is open about the fact that sometimes tensions emerged within the group, she is quick to point out that an obsession with this friction is indicative of sexist assumptions. “This is one of the issues that tends to come up in articles that people write, because for some reason people are fascinated by the idea that it was difficult, or that we had fights, or that it all sounded very nice but it probably didn’t work so well,” says Stansfield. “Yes there were tensions, because we were working in a very intense way together… But I think that’s been overblown and it’s actually quite anti-women.”

Still from ‘A Question of Choice’ (1982). Image: ‘A Question of Choice’/Vimeo.

The process of making a project was as collaborative as possible, in line with the non-hierarchical approach favoured by the Women’s Liberation Movement at the time, and in general the women tried to work as far as possible on an equal level, although Woodley acknowledges there were inevitably limitations to this. “We all used to work on the script together…we would toss around ideas, write things down, revise them,” says Woodley. “The idea was that we would rotate roles like camerawork, director, sound, editing, lighting, so that we all got a chance to learn on the job as it were. That worked up to a point.”

Although their principles remained sound, over time the practicalities of filmmaking meant that members did begin to specialise. “We started off with good intentions, but we realised that film is quite technical,” says Woodley. After a while, it was good to spend more time getting to grips with one particular technical aspect of things.” Over time, Woodley became fascinated by editing, and ended up applying for a grant to study filmmaking. This meant that by the time it came to editing A Woman Like You she was already best placed to take a lead on the editing. She would work on the film in the day, until about five o’clock, when the others would arrive with their kids and together they would discuss the day's work. “We would have sessions where we all look at how the editing was coming along and make comments about it together. And I would sometimes make revisions or I would suggest something and alter it while everybody was there.”

Inevitably not every editorial decision was unanimous or every job entirely shared, but like Stansfield, Woodley’s primary memory is one of sisterhood. “I miss that [solidarity]” says Woodley. “And I miss my friends, obviously. We worked together so well for so long.” A while ago, Woodley bumped into a woman with whom she had worked alongside in that early group decades earlier and was struck by the bond they shared. “We still immediately had that connection…the women who were in that original consciousness raising group told each other things we hadn’t even told our partners.”

A breakthrough moment for the Co-op came in the early 1980s with the launch of Channel 4. Part of the remit of the channel was to support innovative film work produced by independent groups regionally. Suddenly, the Co-op had access not only to new pots of funding but also to much larger audiences. Having spent their early years touring reels around community centres, they now had an opportunity to reach nationwide television audiences.

The title card for the film ‘That’s No Lady’ (1977), a film intercutting scenes of domestic abuse with a male comedian telling jokes about women. Image: ‘That’s No Lady’/Vimeo.

It was at this pivotal moment that Stansfield moved to Sheffield, met Woodley and became involved in the collective. “I was kind of interested in what they were doing, but I never imagined I would get into it myself,” Stansfield remembers. Slowly she became involved, helping with administrative tasks alongside her degree. By the time she graduated in 1983, Stansfield was able to immediately join as a paid member of the collective.

Within a few years she had made her directorial debut with Bringing It All Back Home (1987), a documentary about the exploitation of female workers in the developing world. “It was crazy, I had never directed before!” Stansfield remembers. “And the first film I directed was going to be on TV, and had quite a large budget, so that was bizarre.” Bringing It All Back Home was picked up by a North American distributor, and has screened many times over the decades in the US and beyond. Stansfield eventually became a freelance filmmaker, a trajectory that would have been out of reach without the Co-op. “It was the flavour of the times really, that everything was opening up,” says Stansfield. “It was extraordinary.”

The Co-op’s boom lasted almost a decade, during which the group made increasingly ambitious productions exploring such diverse topics as child poverty in Thatcher’s Britain, gay Olympians and Sheffield’s “buffer girls”. By the early 1990s however, this golden age of public funding had come to an end and, unwilling to make the compromises needed to operate commercially, the Co-op decided to formally close. Stansfield moved on but became an unofficial custodian of the Co-op’s films, renting them out for occasional public screenings. For a couple of decades though, that was pretty much that.

Recently however, there has been a resurgence of interest in the Co-op. “Within the past ten years people have started asking about the films,” says Stansfield, who along with Woodley, looks after the group’s legacy. “And that’s quite a surprise, quite gratifying as well.” By the mid-2010s, Stansfield was inundated with requests for the films from researchers and curators, so she turned to local archivist Alex Glenn Wilson for help with dealing with digitising the collection. Now films which previously were buried in reels stashed in attics are available to watch for free online and this new availability has only served to increase interest in the Co-op’s history.

Filming in Walkley (L-R: Christine Bellamy and Jenny Woodley). Image: Caroline Laidler.

A key reason why these films remain so resonant is because of their continuing topicality. “Seventies and eighties politics are very resonant right now,” says Wilson, highlighting how pressing current issues such as growing social inequality, resurgent right wing backlash and polarising “culture wars” rhetoric hark back to Thatcher’s Britain. “The themes that these films cover locally, politically, socially…what was happening in the eighties is rearing its ugly head again in many ways right now.” “I think all of the films that we made, are surprisingly, still relevant,” agrees Woodley. “If you look at Not Just A Pretty Face…the amount of violence against women if anything has increased, not diminished. We’ve seen what’s happened in the US about abortion rights. A Woman Like You is horribly relevant still. Maybe that’s why our films are suddenly being shown again?”

Five decades have passed since the Co-op first began and for the collective’s surviving members that march of time has come with a realisation that making the work accessible is an urgent issue. Although it's been decades since they shared the same house, and they haven’t worked together as filmmakers for many years, nowadays Woodley and Stansfield remain connected by their shared work in protecting the Co-op’s archive. “I think what Jenny and I have realised is that this body of work, which we’ve been involved with in different ways, at different times, is going to live longer than we are,” says Stansfield. “Therefore we have this desire and this commitment to say ‘let’s make sure it is remembered,’ so people can make use of it in whatever way they want, and it doesn’t just disappear.”

Ultimately, the films of the Sheffield Film Co-op are more than simply esoteric pieces of local history — they are a crucial part of the story of independent film across the UK. “Legacy-wise, this notion that independent production could become a reality here was really inspirational to loads of people,” says Wilson. “The Co-op were at the forefront of that really. It’s a bit of a leap, but I don’t think it’s totally fanciful. One can chart a lineage from those days to something like Warp Films…that kind of spirit, that ethos to do something here where there is no broadcaster. It’s an independent spirit still, it has to be, in order to sustain itself. And I think those roots were set by the Co-op.”

Beyond that local and national lineage, the Co-op’s work continues to reach new audiences around the world. As the co-founder of Invisible Women, a feminist film collective based in Edinburgh and Glasgow, I have often screened the Co-op’s work myself, most recently as part of a film festival in Athens. As I watched a packed screening room sit rapt in front of A Question of Choice — subtitled to help a Greek audience keep up with the film’s broad Yorkshire accents — I was struck once again at the power of film to transcend decades and cultures. As long as the issues that the Co-op spoke about remain relevant, then I’m confident that their films will keep connecting in this way, inspiring future generations of film enthusiasts and frustrated feminists for many more years to come.